The book

MARIA MUSIOL

VITTORIA COLONNA.

A Woman’s Renaissance

ISBN: 978-3-7450-4134-7

Price: 27,09 Euro

Berlin Epubli GmbH 2017

BUY THE BOOK:

a) direct from the publisher

www.epubli.de

Books are delivered abroad

From amazon.de

In case of problems consult:

mariazitadrmusiol@gmail.com

TAKE A VIEW IN THE BOOK

Google books.com

Just insert in google: Maria Musiol + Vittoria Colonna + A Woman’s Renaissance.

You will be taken to my book at epubli.de.

Why the author wrote this biography

Why write a biographical study about Vittoria Colonna? Does a concise profile not serve the purpose? Has a decade of research work been necessary to get an idea of a single woman of the sixteenth century?

Never has my impetus slackened to illuminate the shadowy afterlife of this celebrated female genius of Italian Renaissance, the only woman in Michelangelo’s life, who enthused about her: “A man in a woman, even a god speaks out of her mouth.”

Why?

Delving into secondary literature confirmed the saddening impression that her genius has constantly been demeaned, because she was a woman. A pastiche of eclectic approaches that were thought sufficient for Vittoria Colonna fragmented her bright personality in a prismatic mirror.

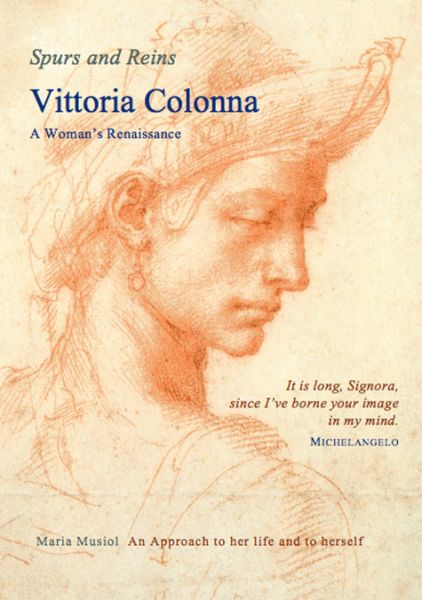

The rumour of her inconspicuous outward appearance has been passed on to the present day, ever since a malevolent contemporary biographer jeered that she, married to handsome Pescara, physically, a glorious specimen of a man, had to develop her mental faculties, because she was no beauty, although Michelangelo, who created the most impressive drawings of her, wished he could change his body into one single eye to rejoice in her beauty to the fullest.

Vittoria’s identity in the frontispiece of this book can be proved by her anorexia confirmed by several eye-witnesses: “She has the skin on the bones”. Above all, it is proved by the coincidence of Michelangelo’s drawing with Paolo Giovio’s painstaking description of her striking physiognomy, her long nose, rich hair, pretty ears, and her precious ear-rings. Regardless this very drawing was labelled as “the head of a young man” in the exhibition of Michelangelo’s drawings (British Museum, London in 2005), albeit provided with a question mark.An entry in Wikipedia reads: “Her poetry excels in technical perfection. But today it is judged as conventional and little authentic.” The arrogance of such a misjudgement and the delusionary confidence in progress are breath taking, as if the latter born were automatically the smarter ones, as if the fact that the poetess was held in high esteem by the great literati of her day was just negligible.

Anthologies flourish that bring together Renaissance women writers, a gender related procedure, because there are no male equivalents. According to the contemporary aesthetics of mimesis, Vittoria leaned on the Petrarchan idiom as the literary model for her sonnets, an indisputable fact that led her critics to focus coincidences with Petrarca and to ignore her authenticity, which, however, is of anthropological interest, because Vittoria Colonna initiated a novel female subject-constitution as an erudite Humanist voiced by the I-Speaker in Vittoria Colonna’s poetry.

The eclectic approach fails the complexity of Vittoria Colonna that was intensified by the fact that she was influenced by the conflicting intellectual and spiritual currents of Renaissance-Humanism and Reformed Theology.

In contrast to a seasoned personality, who, calculable and easy to see through, moves within a firmly set frame, Vittoria Colonna irritates her readers by her unexpected otherness. Occasionally she forces them to correct their preconceived image of women.

Her intellectual liveliness and creativity, her irresistible drive for female self-fashioning in various cultural areas necessitate the representation of Vittoria Colonna live. In her individualism she is only accessible in the immediacy of her active and spiritual life she registered in its subjectivity by means of her I-Speaker in her sonnets. A kind of open biographical writing is necessary, because her female renaissance originated in the interaction of her life and her poetising.

Approach to historic truth about Vittoria Colonna is possible, because conscientious historians of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have made this singular woman accessible by exemplary editions of her sonnets, letters, and prose.

Walking in the footsteps of the Greek historian Thukydides, the author refrained from evaluation, contenting herself with the historic truth about Vittoria Colonna, describing who and how she had really been, on the basis of her sonnets, prose, letters and contemporary evidence.